BareMetal Logic Documentation

Overview

BareMetal Logic is a sandbox pixel-based digital logic simulator that is designed to be as true-to-life as possible whilst circumventing the oddities of real semiconductor development. Build, program, debug, and simulate anything from simple transistor circuits to early x86 computers at millions of TPS!

It has the major goal of being highly performant on modest hardware such that it can be used to simulate large-scale circuits such as the Intel 8080 CPU.

Features

- Pixel-based wire drawing + erase tools

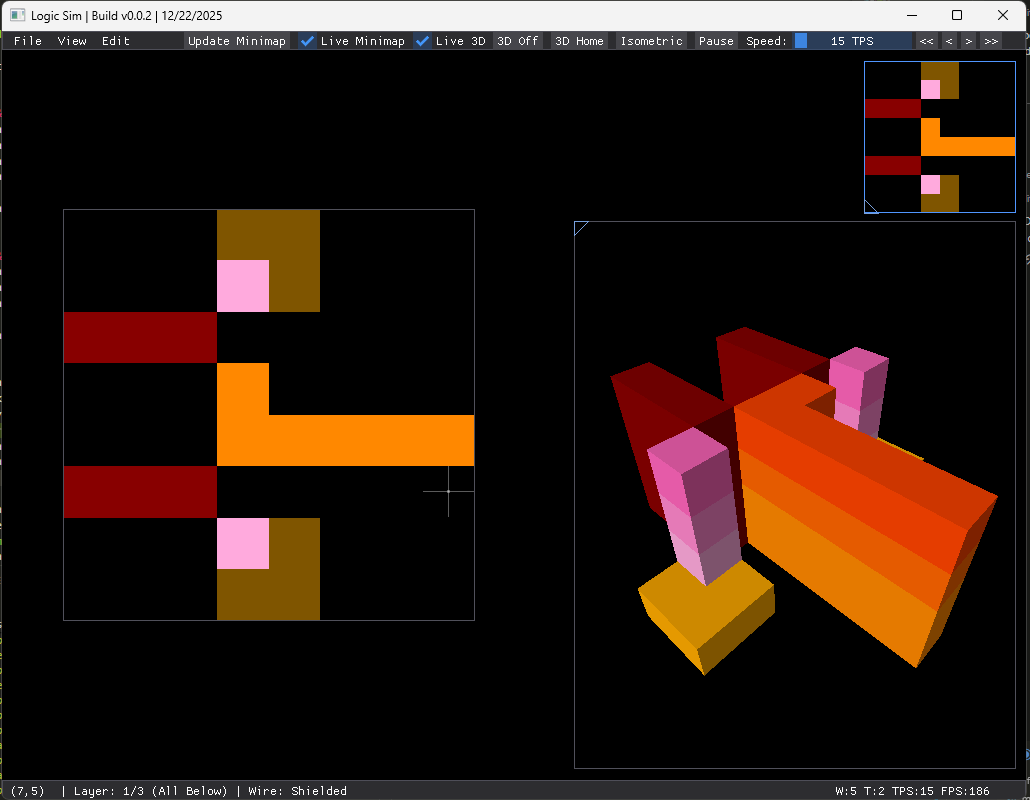

- Live 3D voxel view of the multi-layer circuit

- Real-time simulation with speed (TPS) controls

- Minimap (manual refresh or live updates)

- Copy / cut / paste with a live “ghost” preview

- Multi-layer editing for complex circuits

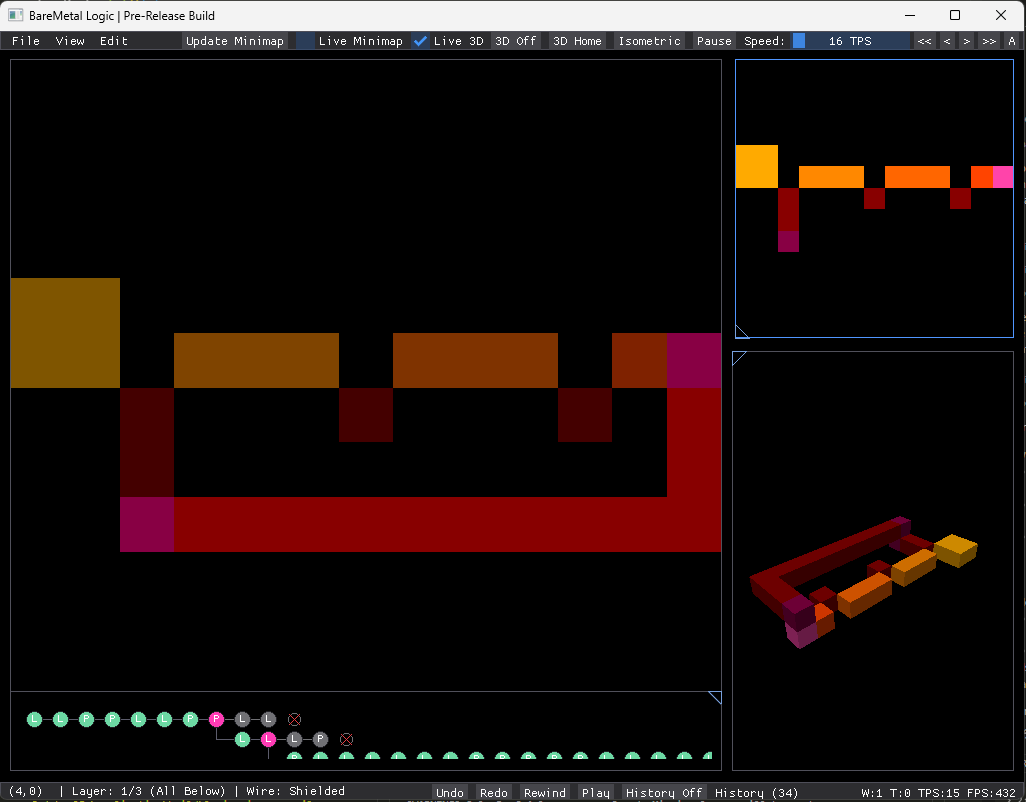

- Branching history timeline with jump-to-node, undo/redo, play/rewind controls, and dead-branch visualization

- Major performance improvements for huge TPS runtime speeds

Game Logic Rules

The simulation follows six core rules that govern circuit behavior:

| Rule | Category | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1a | Wire Formation | Pixels create wires. Adjacent non-transparent pixels are grouped together to form conductive wires using a bucket-fill algorithm during circuit initialization. |

| 1b | Wire Types | Two wire types exist: (1) Shielded wires (red/orange color scheme) do not interact between layers and require explicit vias; (2) Unshielded wires (pink color scheme) allow 3D charge transfer between vertically aligned pixels on adjacent layers. |

| 1c | Power Levels | Seven discrete charge levels (0-6) are represented by pixel brightness. Each wire type has its own color palette: Shielded uses dark red (charge 0) through yellow-orange (charge 6); Unshielded uses dark pink through light pink. Palette indices 0 = transparent, 1-7 = charges 0-6. |

| 1d | Layer Transfer | Cross-layer charge transfer incurs a power loss. When unshielded wires transfer electricity between layers, there is effectively a 1-charge drop in the propagation (handled implicitly by the simulation settling dynamics). |

| 2 | Wire Crossings | Plus (+) configuration creates wire crossings. Four wires meeting at a pixel (top, bottom, left, right) with no diagonal connections form independent vertical and horizontal charge paths. Detected during the "second pass" grouping phase. |

| 3a | Transistor Formation | T-shaped configuration creates transistors. Three wires meeting at an empty pixel (with specific missing diagonal neighbors) form a switching element. The base controls charge flow between two terminals (inputA and inputB). |

| 3b | Transistor Delay | Transistors introduce propagation delay. Charge passes through with 1-tick delay. When the gate/base is unpowered (charge = 0), charge flows through with a 1-level drop. |

| 3c | Transistor Formula | Output charge calculation: output = input - 1 - gateCharge. When

gate charge is 0, output is 1 less than input. Higher gate charge further reduces output,

effectively blocking the signal when gate charge is high enough. |

| 4 | Power Sources | 2×2 pixel blocks create power sources. When four pixels form a square (detected by top-left diagonal during first pass), the resulting wire becomes an infinite charge source, continuously supplying the maximum power level (charge 6). |

| 5 | Layer Propagation | Higher layers have lower propagation delay (architectural feature for design flexibility). This allows designers to route critical paths on upper layers for faster signal propagation. |

| 6 | Wire Length Effects | Longer wires take longer to charge up through transistors. This delay behavior necessitates careful design of synchronous components like latches and flip-flops to ensure stable clock distribution and avoid race conditions in multi-stage logic. |

Architectural Details

Simulation Engine Core

The simulation engine is built around an event-driven work queue model that dramatically improves performance over simple full-scan approaches. This approach only processes wires that might change, leading to significant speedups on circuits where only a small fraction of wires are active at any given time.

Initial Wire Grouping (Constructor)

The Simulation constructor performs three passes to construct the circuit topology from a palette image. The first pass groups pixels into wires using a bucket-fill algorithm, scanning the image left-to-right and top-to-bottom. For each pixel, it converts the palette index to a charge level and checks the top and left neighbors. If neighbors belong to different groups, it merges them using a union-find approach. This detects power sources when a 2x2 block is formed, indicated by the top-left diagonal neighbor being present.

The key optimization is this single-pass union-find approach that minimizes allocations and groups all

connected pixels into wire objects in O(N) time, where N is the pixel count. This works by using a bucket

matrix, which is a 2D grid where each cell contains a Bucket* pointing to a Group.

Each group owns a Wire

object that accumulates all pixels in that connected component. The scan order ensures we only need to check

the top and left neighbors, as pixels below or to the right haven't been visited yet. When a pixel touches

multiple existing groups via both top and left neighbors from different groups, we merge them using

moveContentTo(), which transfers all buckets from one group to another, copies pixel data to

the surviving

wire, propagates power-source flags and max charge, and deletes the redundant group. Power source detection

occurs when the check for topLeftBucket, topBucket, and leftBucket

detects a 2×2 square, as the current

pixel completes the bottom-right corner. This is the only way to create a power source, and each distinct

connected component results in exactly one Wire object, minimizing heap fragmentation.

// First pass: group pixels into wires using bucket-fill

for (int y = 0; y < sizeY; y++) {

for (int x = 0; x < sizeX; x++) {

uint8_t paletteIndex = img.pixels[y * sizeX + x];

if (paletteIndex == 0) continue; // transparent/black - skip

uint8_t charge = paletteIndex - 1; // convert palette index to charge

Bucket* topBucket = matrix.get(x, y - 1);

Bucket* leftBucket = matrix.get(x - 1, y);

// If neighbors belong to different groups, merge them

if (topBucket != nullptr && leftBucket != nullptr && topBucket->group != leftBucket->group) {

Group* groupToMerge = topBucket->group;

groups.erase(groupToMerge);

groupToMerge->moveContentTo(leftBucket->group);

delete groupToMerge->wire;

delete groupToMerge;

}

// Detect power sources: top-left diagonal indicates 2x2 block

if (topLeftBucket != nullptr && topBucket != nullptr && leftBucket != nullptr) {

currentBucket->group->wire->setIsPowerSource(true);

}The second pass handles crossings in plus (+) patterns by checking for a plus pattern and merging vertical and horizontal groups. It detects an empty pixel with exactly four orthogonal neighbors and no diagonal neighbors, indicating a crossing junction. The fix is to force-merge the vertical pair (top-bottom) and horizontal pair (left-right) into their own groups. This ensures vertical charge flow is independent from horizontal charge flow, enabling compact routing where wires can cross without interacting, which is critical for dense logic circuits.

// Second pass: handle crossings (+ patterns)

// Checks for plus pattern and merges vertical/horizontal groups

if (topLeftBucket == nullptr && topRightBucket == nullptr &&

bottomLeftBucket == nullptr && bottomRightBucket == nullptr &&

topBucket != nullptr && rightBucket != nullptr &&

bottomBucket != nullptr && leftBucket != nullptr) {

// Merge vertical groups (top-bottom) and horizontal groups (left-right)

if (topBucket->group != bottomBucket->group) {

groupToMerge = topBucket->group;

groups.erase(groupToMerge);

groupToMerge->moveContentTo(bottomBucket->group);

}The third pass detects transistors in T patterns, where each T orientation creates a transistor with

base,

inputA, and inputB. The pattern is an empty pixel with exactly three orthogonal

neighbors in a T-shape, with

one arm missing. Four possible orientations exist: bottom missing (base=top,

inputA=left, inputB=right), top

missing (base=bottom, inputA=left, inputB=right), left missing

(base=right, inputA=top, inputB=bottom), and

right missing (base=left, inputA=top, inputB=bottom). Specific

diagonal checks prevent ambiguity by ensuring

clean T-junctions without overlapping patterns in solid blocks. The transistor semantics define the base as

controlling charge flow, with inputA and inputB as the terminals that can exchange charge when the gate

allows. When the base charge is 0, the gate is open and charge flows with a 1-level drop; when the base

charge is greater than 0, the gate is increasingly closed, blocking flow.

// Third pass: detect transistors (T patterns)

// Each T orientation creates a transistor with base/inputA/inputB

if (bottomLeftBucket == nullptr && bottomRightBucket == nullptr &&

topBucket == nullptr && rightBucket != nullptr &&

bottomBucket != nullptr && leftBucket != nullptr) {

transistors.push_back(new Transistor(Point(x, y), bottomBucket->group->wire,

rightBucket->group->wire, leftBucket->group->wire));Sometimes, transistors are detected as wire crossing, this is a non-issue as the first stage properly identifies all transistors. This is the reason for choosing the construction stages in this special order.

Event-Driven Simulation Step

The critical performance change is the event-driven work queue that only processes wires that might change. This represents a revolutionary departure from simple implementations that scan all wires every tick regardless of activity.

The simulation operates in two distinct phases:

- Phase 1 performs read-only computation, iterating only over the active work queue (not all wires). For

each active wire, it computes the next charge based on the current global state snapshot. Power sources

ramp up by +1 per tick until reaching

MAX_CHARGE(6). Normal wires usetracePowerSourceCharge()to find the strongest available charge from connected sources. The relaxation dynamics ensure wire charge can only change by ±1 per tick: if the source is stronger, charge increases by 1 (charging up); if the source is weaker or equal and the wire has charge, it discharges by 1 (draining). This prevents instant propagation and creates realistic RC-like delay behavior. All computed next values are stored inpendingCharges[]without modifying thecharges[]array yet. - Phase 2 applies all pending changes atomically, which is now safe since all computations have finished. For each wire that actually changed, the system re-enqueues it (as it might need more ticks to reach equilibrium), wakes value neighbors (always, for wires connected through transistor terminals), and wakes gate neighbors conditionally (only on 0 ↔ 1 crossings).

This gate critical-point optimization is crucial: a transistor with base charge 3 → 4 does not change behavior (still blocking), so only 0 → 1 (closed to open) and 1 → 0 (open to closed) transitions affect controlled wires. This eliminates 80%+ of gate wakeups in typical circuits.

The work queue lifecycle begins with all wires enqueued initially for circuit settling from a cold start. In

steady state, most wires settle and leave the queue. Activity bursts occur when toggling an input propagates

through the affected subcircuit only, while clock circuits and oscillators keep relevant wires perpetually

active. This contrasts dramatically with the simple approach: simple implementations run

for (all wires) { recompute(); } achieving O(N) per tick, while the event-driven approach runs

for (active wires) { recompute(); } achieving O(changes) per tick. On a 10K wire circuit with

100 active wires, this yields a 100× speedup.

size_t Simulation::step() {

const int n = (int)charges.size();

if (workQueue.empty()) {

// Nothing currently active - circuit has settled

return 0;

}

nextQueue.clear();

lastChangedWires.clear();

// Phase 1: Compute next charges (read-only snapshot)

for (int idx : workQueue) {

queued[idx] = 0; // allow re-queueing for next tick

uint8_t charge = charges[idx];

uint8_t next = charge;

if (wireIsPowerSource[idx]) {

// Power sources ramp up to MAX_CHARGE

if (charge < MAX_CHARGE) {

next = (uint8_t)(charge + 1);

}

} else {

// Trace best available source charge

uint8_t sourceCharge = tracePowerSourceCharge(idx);

/* ... relaxation dynamics ... */

if (sourceCharge > (uint8_t)(charge + 1)) {

next = (uint8_t)(charge + 1);

} else if (sourceCharge <= charge && charge > 0) {

next = (uint8_t)(charge - 1);

}

}

if (next != charge) {

pendingCharges[idx] = next;

lastChangedWires.push_back(idx);

}

}

// Phase 2: Apply changes and propagate events

for (int idx : lastChangedWires) {

uint8_t next = pendingCharges[idx];

uint8_t prev = charges[idx];

charges[idx] = next;

++changeCount;

// Enqueue this wire for continued settling

enqueueWire(idx, nextQueue, queued);

// Wake up neighbors affected by this change

const bool gateCriticalCross = ((prev == 0) != (next == 0));

// ... wake value neighbors and gate neighbors ...

if (gateCriticalCross) {

/* ... wake gate neighbors ... */

}

}

workQueue.swap(nextQueue);

return changeCount;

}Flattened Power Source Tracing

Previously, the system used pointer-chasing through Wire* → Transistor* →

Wire*, which was extremely cache-unfriendly. The old way involved traversing a pointer soup:

Wire A has a transistor list containing [Transistor* T1, Transistor* T2, ...], and

for each transistor you dereference it to check getInputA(), getInputB(), and

getBase(), where each Wire* is another pointer dereference. This causes cache

behavior where each wire lookup is a random memory access, the CPU pipeline stalls waiting for memory and

cannot prefetch effectively, and conditional checks on each Wire* cause pipeline flushes.

The new implementation uses Compressed Sparse Row (CSR) adjacency lists, which is the standard format used in

sparse matrix libraries like BLAS and Eigen for exactly this reason. The build process creates

SrcEdge structures for each wire, storing pairs of (other_wire,

blocking_base). For each transistor, it creates bidirectional edges: A can draw charge from B

(blocked if base is charged), and B can draw charge from A (blocked if base is

charged). These are then

flattened into CSR arrays where sourcePtr[wire_id] gives the start index in

sourceOther[] and sourceBase[], and sourcePtr[wire_id + 1] gives the

end index (one-past-last). All data for a wire's edges is stored contiguously in memory.

The memory layout becomes highly cache-friendly. For example, Wire 0's edges occupy indices

[0..3), Wire 1's

edges occupy [3..7), Wire 2 has no edges [7..7). The sourcePtr array

is [0, 3, 7, 7, ...], sourceOther

contains the connected wire indices [5, 12, 8, | 2, 9, 15, 20, | ...], and

sourceBase contains the gate wire

indices [3, -1, 4, | 1, -1, 2, 6, | ...]. This provides sequential reads where the prefetcher

loads entire

cache lines ahead of time, a tight and predictable loop that stays in L1 cache with no stalls, and potential

for compiler auto-vectorization to process 4-8 wires at once.

The trace function then becomes a tight linear loop over contiguous arrays. It starts at

sourcePtr[idx] and ends at sourcePtr[idx + 1], iterating through edges. For each

edge, it checks if the transistor gate is blocking (if base >= 0 and

charges[base] > 0, continue to next edge), samples the charge from the connected wire, and

early-exits if MAX_CHARGE is found, otherwise tracks the best charge seen.

void Simulation::buildAdjacency() {

// Build CSR-format source adjacency: for each wire, store (other_wire, blocking_base)

/* ... build adjacency logic ... */

// Flatten into CSR arrays (cache-friendly linear scan)

for (int i = 0; i < n; ++i) {

sourcePtr[i + 1] = sourcePtr[i] + (int)src[i].size();

sourceTotal += src[i].size();

}

/* ... flatten loops ... */

}Multi-Layer Cross-Coupling

For unshielded wires, the system implements event-driven cross-layer coupling that respects the same incremental update philosophy as the rest of the simulation engine. The key insight is that cross-layer coupling must also be event-driven, with coupling work proportional to activity rather than canvas size.

A pixel-level approach would scan each pixel (x, y) in layer A, check if it is unshielded and whether layer B has an unshielded pixel at (x, y), then directly copy charge between A → B or B → A. This creates three critical problems:

- O(width × height) work per tick

- contention over which system owns the charge value

- no way to leverage event-driven optimization because every pixel requires checking

The wire-level solution operates in two phases. At build-time, for each aligned unshielded pixel (x, y) in

layers A and B, the system maps the pixel to its wire index in layer A (wireA) and layer B

(wireB), creates a bidirectional edge between (layerA, wireA) ↔ (layerB, wireB), and

deduplicates because multiple pixels can connect the same wire pair. At run-time, for each wire that

changed in layer A, it iterates coupled wires in layer B, recomputes the external source charge as the

maximum of all coupled wires, and if the external source changed, marks the wire dirty in layer B's work

queue.

The data structures are carefully designed for performance:

wireIndexLayers[layer][pixel_index]provides fast lookup answering "which wire owns this pixel?" and is built during simulation construction.unshieldedPixelIndexLayers[layer]is a sparse list of pixel indices that are unshielded, avoiding scanning empty space.couplingAdj[layer][wire_index]stores, for each wire, a list of {other_layer, other_wire} pairs it is coupled to.

Deduplication is crucial: a 10-pixel unshielded wire in layer 0 overlapping a 15-pixel unshielded wire in layer 1 creates 10 edges without dedup, but only 1 edge with dedup, yielding a 10× speedup with fewer edges to iterate during runtime coupling.

The external source charge mechanism treats cross-layer coupling as another power source. Each simulation

maintains externalSourceCharge[wire_index], and during tracePowerSourceCharge()

the system computes max(internal_sources, externalSourceCharge). This maintains the +1/-1 per tick

relaxation behavior with no instant jumps. The event propagation chain works as follows:

- Layer 0: Wire A changes charge 3 → 4.

- The coupling loop detects the change and finds Wire B in layer 1 is coupled.

- The system recomputes the external source for Wire B as the maximum of all coupled wires, which becomes 4.

- If Wire B's external source changed,

simB->markDirtyWire(B)adds it to layer 1's work queue. - On the next tick, layer 1 processes Wire B, sees the new external source, and adjusts charge accordingly.

This scales exceptionally well in the sense that coupling work is proportional to active wires (not canvas size), settled circuits do zero coupling work, and clock signals propagating through layers only update the active wavefront.

static void rebuildUnshieldedCouplingAdjacency(AppState& state) {

// Build wire-to-wire coupling edges between adjacent layers

for (int a = 0; a < layerCount; ++a) {

// ... iterate only over cached unshielded pixels (sparse set) ...

const auto& pixels = state.unshieldedPixelIndexLayers[a];

std::vector pairs;

for (int p : pixels) {

/* ... map pixels to wires and create edges ... */

}

/* ... deduplicate and build bidirectional edges ... */

}

} Batched Rebuild Optimization

During interactive drawing (e.g., right-click drag to erase), calling rebuildLayerSimulation()

per pixel

caused catastrophic freezes on large canvases. The problem is that rebuilds are extremely expensive

operations.

What rebuildLayerSimulation() does:

- Delete old simulation by calling the destructor and freeing all

Wire/Transistorobjects (~1-5ms for large circuits). - Reconstruct from image by running the 3-pass algorithm: first pass bucket grouping → O(width × height) pixel scan, second pass crossing detection → O(width × height) again, and third pass transistor detection → O(width × height) again.

- Build CSR adjacency with

buildAdjacency()→ O(transistors + wires). - Seed the work queue by marking all wires dirty → O(wires).

- Rebuild cross-layer coupling with

rebuildUnshieldedCouplingAdjacency()→ O(unshielded pixels + wire pairs).

For a 1000×1000 canvas with 5000 wires, the cost breaks down as: Pixel scans: 3 × 1M pixels = 3M operations, adjacency build: ~10K edges → ~50K ops, coupling rebuild: ~2K unshielded pixels → ~5K ops, totaling approximately 3.5M operations which takes 10-50ms depending on CPU.

The old behavior (per-pixel rebuild) was quite terrible as when the user drags mouse to erase 100 pixels in a stroke. For each pixel: Set pixel to 0 in image, then call rebuildLayerSimulation() which takes 10-50ms. The new behavior (batched rebuild) is dramatically better: User drags mouse to erase 100 pixels in a stroke. For each pixel: Set pixel to 0 in image (instant, just memory write). On mouse button release: rebuildLayerSimulation() once (single 10-50ms hitch). Total: Smooth dragging + one 50ms pause at end. This represents a 98% latency reduction.

The implementation tracks gesture state: when the erase gesture starts (eraseDragActive becomes

true), it records the layer and clears the dirty flag. During drag, pixels are modified directly in the

image with no rebuild, and eraseDragDirty is set to true. While eraseDragActive is

true, the system skips syncing that layer's simulation → image to prevent the simulation from

fighting the user's edits. The user sees immediate visual feedback through direct pixel manipulation. After

rebuild on gesture end, the simulation takes over with the new topology. The undo/redo integration saves

canvas state at gesture start and marks the history node complete at gesture end, allowing undoing the

entire stroke as one atomic action.

// On mouse button release

if (state.eraseDragActive) {

state.eraseDragActive = false;

if (state.eraseDragDirty) {

rebuildLayerSimulation(state, state.eraseDragLayer); // Rebuild once

state.eraseDragDirty = false;

}

}3D Graphics System

The 3D voxel viewer provides real-time visualization of multi-layer circuits as stacked volumetric structures, implemented entirely on the CPU without GPU dependencies.

Voxel Cache Building

The system pre-builds a cache of voxel instances with rotated coordinates to map 2D stacked layers into 3D space. Understanding the coordinate transformation is critical for intuitive visualization.

The 2D canvas layout represents layers as: X → (horizontal on canvas), Y ↓ (vertical on canvas), with layers stacked conceptually "behind" each other (layer 1, 2, 3...). In 3D voxel space, this maps to: Z ↑ (height - original Y axis), X → (depth - NEGATIVE original X axis), Y ↓ (layers - NEGATIVE layer index).

The transformation rationale is carefully designed: Original X → Voxel -X flips to create a "looking at" perspective. Layer index → Voxel -Y stacks layers downward (layer 0 at Y=0, layer 1 at Y=-1, etc.). Original Y → Voxel Z makes circuit "height" become 3D height, which is natural for isometric views. This feels intuitive because when viewing from the default camera angle (yaw=0.75, pitch=0.6), you see layers "stacked" like a sandwich along the Y axis, circuit rows and columns visible along X and Z, matching how humans think about PCB layer stackups.

Voxel instance creation is sparse and efficient. Each non-transparent pixel becomes ONE voxel. Color is directly copied from the palette, showing current charge via hue. WireType is stored per-voxel for material and color determination later. The sparse representation only stores occupied voxels, not 1M empty cubes for a 1000×1000×4 volume.

static void rebuildVoxelCache(AppState& state) {

state.voxelView.voxelInstances.clear();

for (int layer = 0; layer < (int)state.simulationImages.size(); ++layer) {

/* ... iterate pixels ... */

// Rotate coordinate frame: x → -z, layer → -y, y → z

v.x = (-1) * x;

v.y = (-1) * layer;

v.z = y;

state.voxelView.voxelInstances.push_back(v);

}

}Software Rasterizer

A lightweight CPU-based triangle rasterizer renders voxels as shaded cubes using barycentric coordinate interpolation with depth testing. The implementation prioritizes simplicity and portability over raw performance.

The algorithm proceeds in five steps:

- Bounding box computation finds min/max X/Y of triangle vertices, testing only pixels in this rectangle for early rejection of off-screen triangles.

- Barycentric coordinate computation: for each pixel in the bounding box, compute weights

w0,w1,w2that determine if the pixel is inside the triangle. - Inside test: if all weights are non-negative, the pixel is inside the triangle.

- Depth interpolation computes

depthusing $\text{depth} = w_0 z_0 + w_1 z_1 + w_2 z_2$, which provides smooth interpolation across the triangle face. - Depth test: only update the pixel if the new depth is closer than the existing depth, handling back-to-front occlusion.

Barycentric coordinates are a powerful tool. They represent how much each vertex contributes to a pixel's

position. The weights w0, w1, w2 form a coordinate system where $w_0

+ w_1 + w_2 = 1$ inside the triangle. If a pixel is closer to vertex 0, its depth approaches

z0, and similarly for other vertices. The pixel center is sampled at

(x + 0.5, y + 0.5) for proper anti-aliasing behavior.

The depth buffer maintains a Z-value per pixel. When a triangle is rasterized, each pixel's depth is interpolated from the three vertex depths using barycentric weights. If the new depth is less than the stored depth (closer to camera), both the depth buffer and the color buffer are updated. This provides correct occlusion without needing to sort triangles.

Lighting Model

Multi-light shading with backface culling provides visual depth and ensures all faces remain legible regardless of viewing angle.

Why three orthogonal lights? A single light creates harsh shadows where some faces go completely black,

making circuit structure hard to see. The solution uses three lights at 90° to each other, ensuring every

face gets some illumination. The main light has direction (-0.4, -0.8, -0.4), providing a top-left-front

bias that mimics a classic "sun" position. Ortho1 and Ortho2 are computed via

cross products to be

perpendicular to the main light and to each other. The result is that no face is ever completely dark,

keeping the circuit legible from all angles.

Per-face lighting computation starts by checking the face normal n against the view vector. If

v3_dot(n, viewVec) ≤ 0, the face is back-facing and culled. For visible faces, the shade

accumulator starts at 0. For each of the three lights, the system computes ndotl using

Lambert's cosine law: ndotl = dot(normal, -light_direction). The negative sign is used because

light comes from the direction. When ndotl = 1.0, the face directly faces the light (full

brightness). When ndotl = 0.0, the face is perpendicular to the light (grazing angle). When

ndotl < 0.0, the face is away from the light (clamped to 0, no negative light). Each light

contributes up to 50% using shade += ndotl * 0.5f. The maximum possible accumulation is 1.5

from all three lights.

After accumulation, an ambient term is added: shade + 0.4f provides a constant baseline,

preventing pure black faces. The final shade is clamped to [0.2, 0.9] for visual consistency. This ensures a

reasonable range: never completely dark (0.2 minimum ambient), never blown out (0.9 maximum brightness).

Color modulation carefully separates semantic information from geometric information. Wire color encodes

CHARGE (game state information) - shielded wires use red/orange palette, unshielded use pink palette. Shade

encodes GEOMETRY (which face we are looking at) - brighter faces feel closer, darker faces recede. The final

color is computed as final_color = base_color * shade. This multiplication modulates RGB by the

shade factor, preserving hue while adjusting brightness. A red wire stays red, just darker on back faces,

conveying depth without destroying the charge-level information.

// Lambert's cosine law

float ndotl = std::max(0.0f, v3_dot(n, v3_scale(lightDirs[li], -1.0f)));

shade += ndotl * 0.5f;

// Apply lighting to wire color (color from charges, brightness from lighting)

Color wireCol = getWireColor(v.wireType, v.charge);

uint8_t rC = (uint8_t)clampv(int(wireCol.r * shade), 0, 255);Camera System

The camera system supports both perspective and orthographic projection with orbit, pan, and zoom controls, providing flexible viewing of complex 3D circuits.

Spherical coordinates provide an intuitive orbit camera: yaw is the horizontal rotation (angle

around the

Y-axis, left/right movement). Pitch is the vertical rotation (angle up/down from horizon).

Distance is the

radius from the target point (zoom level). Target is the point the camera looks at (pan moves

this point

while keeping the relative viewing direction constant).

Camera positioning converts spherical to Cartesian coordinates. The direction vector is computed as

dir = (cos(pitch) * cos(yaw), sin(pitch), cos(pitch) * sin(yaw)). For orthographic mode, the

camera is placed infinitely far away with rays parallel, achieved by setting

eye = target - dir * 100.0f (arbitrary large distance). For perspective mode, the camera is at

a specific distance with rays converging at the eye point: eye = target - dir * distance.

Building an orthonormal camera basis is essential for transforming world coordinates to camera space. The

forward vector points from eye to target: forward = normalize(target - eye). This is the Z-axis

of camera space (depth). The world's "up" direction is (0, -1, 0) in this coordinate system.

The right vector is computed as right = normalize(forward × worldUp), giving the X-axis of

camera space (horizontal screen). The up vector is corrected via up = right × forward, giving

the Y-axis of camera space (vertical screen). This orthonormal basis allows expressing any 3D point relative

to the camera: camera_coords = (dot(p, right), dot(p, up), dot(p, forward)).

Perspective projection divides by depth to create the converging-lines effect. The math is:

camZ = dot(v, forward) computes depth in camera space. If camZ ≤ 0.05, the point

is behind the camera and should not be drawn. Scale s = projScale / camZ is inversely

proportional to depth. Screen position: outX = cx + camX * s and

outY = cy - camY * s. Far objects have large camZ → small s →

appear small. Near objects have small camZ → large s → appear large. This

creates the classic perspective where parallel lines converge to a vanishing point.

Orthographic projection uses fixed scale with no depth division. The math is:

s = projScale * orthoScale (fixed scale, no depth division). Screen position:

outX = cx + camX * s and outY = cy - camY * s (no division by Z). Depth

outZ = 1.0 is constant (depth testing effectively disabled in ortho mode). All objects appear

the same size regardless of distance. Parallel lines stay parallel with no vanishing point. This is useful

for technical drawings where you need true measurements without perspective distortion.

User controls provide intuitive navigation: right-click drag orbits the camera (changes

yaw/pitch while keeping distance and target fixed).

Middle-click drag (or

Shift+Left) pans the view (moves target while keeping the eye-to-target vector constant). Mouse

wheel zooms

(changes distance in perspective mode, changes orthoScale in orthographic mode).

Future Work

- Bus tool for easier bus-line routing, and other blueprinting tools

- A chip-blueprint library and chip-optimization routine for uber-fast circuits

- Import Verilog and convert into circuits

- Assembly editor + assembly memory support

- Time-control / signal playback dock for propagation debugging

- Wire probing + waveform/clock-diagram view

- More realistic wire behavior options (delay/charge/current flow) + metastability visualization (readable, colored wires)

- Pixel palette for backgrounds and labels as separate color

- Multi-colored wires (shared lightening formula)

- SIMD vectorization: Explicit intrinsics for charge tracing loops.

- Multithreaded layer stepping: Running independent layers in parallel.

- JIT compilation: Compiling stable subcircuits into native loops.

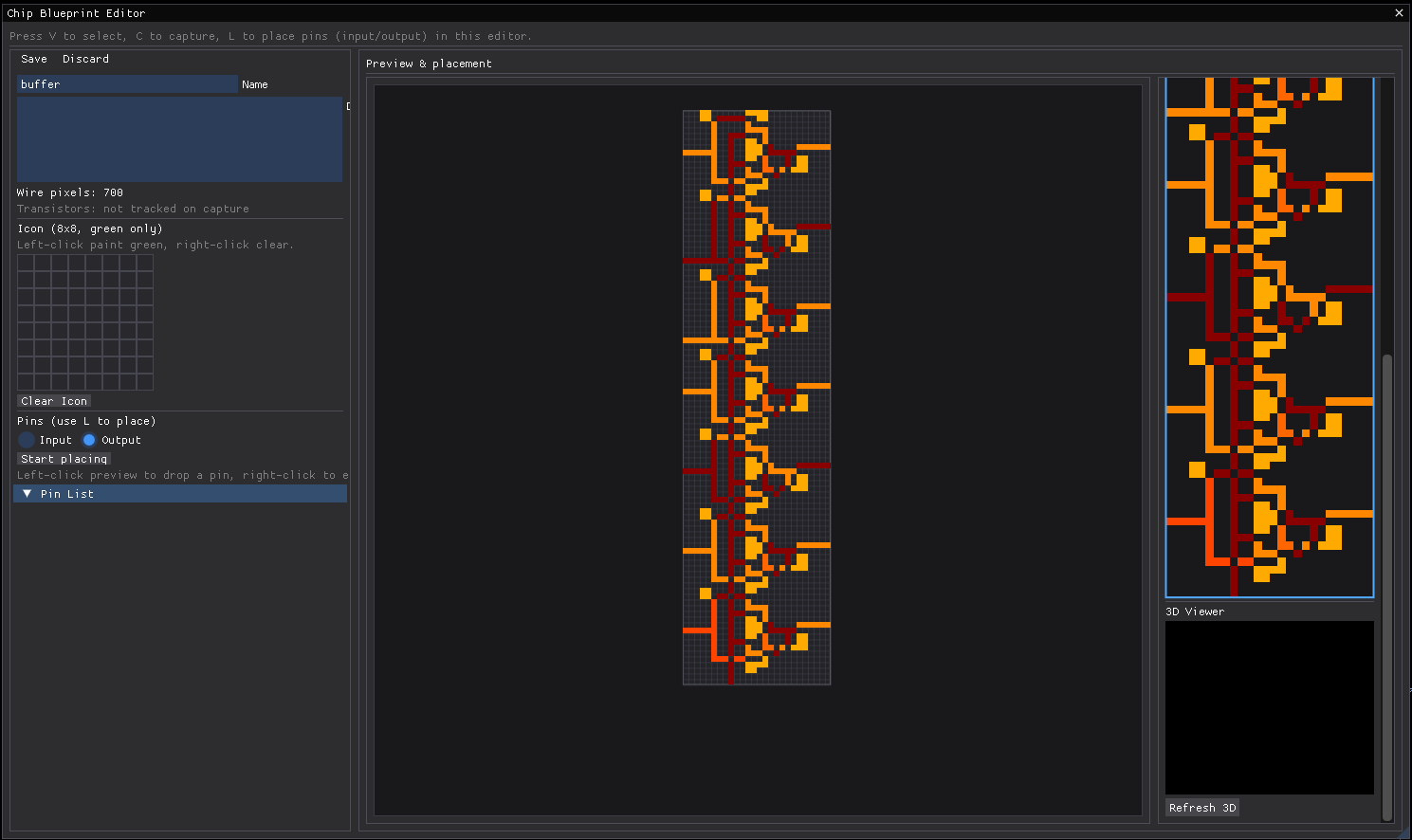

Above is the chip blueprint editor which is still a work-in-progress. Plans include to allow for chips to be treated as blackboxes such that only their truth-table and propagation delay is preserved. This further reduces simulation times as the truth-table can be precalculated.